October was a relatively calm month in the securities markets. On 17 October, the European Central Bank lowered its short-term interest rates by 0.25 percentage points. Since the decision was widely anticipated and already priced into stock markets, it elicited little reaction from participants.

However, it is worth noting that in October, the yield on Germany’s ten-year risk-free government bonds actually rose by 0.2 percentage points instead of falling. A similar reaction occurred a month earlier in the US, when following the Federal Reserve’s decision to lower short-term interest rates by 0.5 percentage points, the yields on ten-year government bonds immediately increased by nearly 0.5 percentage points.

This suggests that markets are far from convinced that central banks have fully brought inflation under control. The problem is that although interest rates in both Europe and the United States are relatively high compared with recent inflation figures, and central banks’ monetary policies may appear rather stringent, government fiscal policy – particularly in the US – seems inexplicably lax, especially given the relatively strong economic environment.

The last decade’s stock market rally may not continue forever

US stock markets, which have been in an upward trend for some time, remained relatively calm in October. The S&P 500 index, which tracks large US companies, gave back 1% of its earlier gains during the month, while EuroStoxx 50, which covers major European companies, lost 3.3% of its value.

An analysis of stock indices and bond markets in October revealed that markets were already pricing in higher chances of Donald Trump being re-elected compared to his opponent. Although both candidates were expected to maintain spending levels significantly exceeding revenues, which would fuel the economic environment, businesses and markets anticipated that a Trump administration would reduce restrictions that are currently hindering economic growth.

That said, Trump cannot be considered a proponent of Reagan-style free-market economics – he proudly declares tariffs to be his favourite policy tool. The anticipated tariffs are the main source of concern for the stock markets of the US’s largest trading partners.

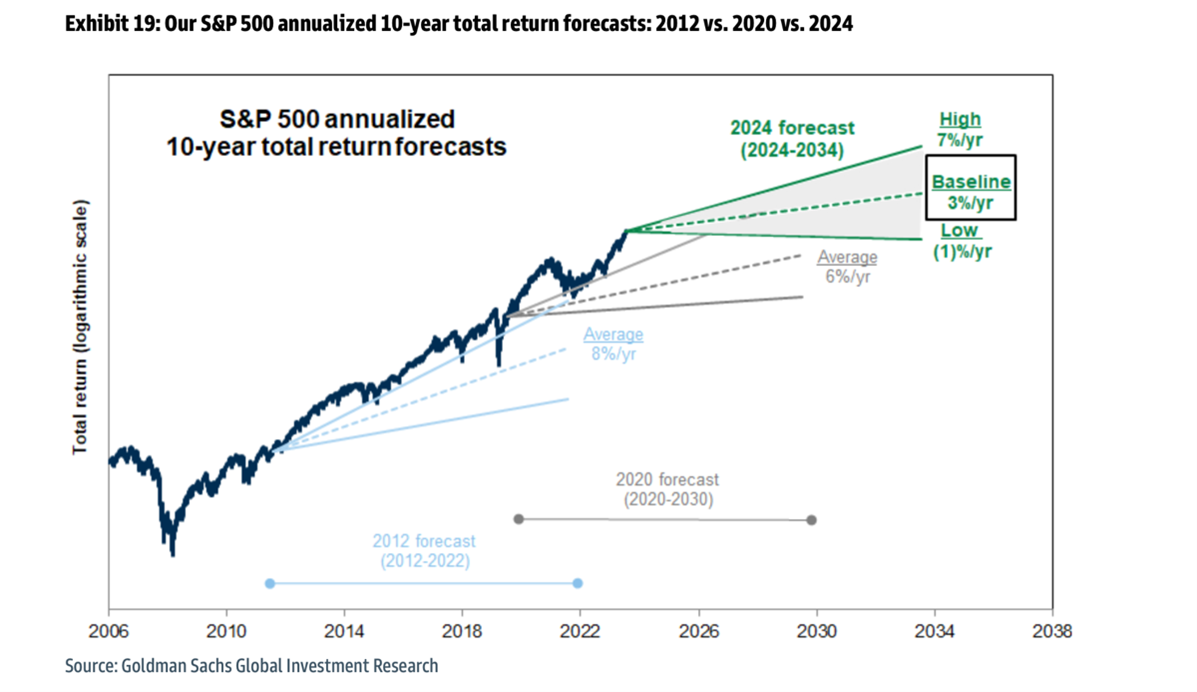

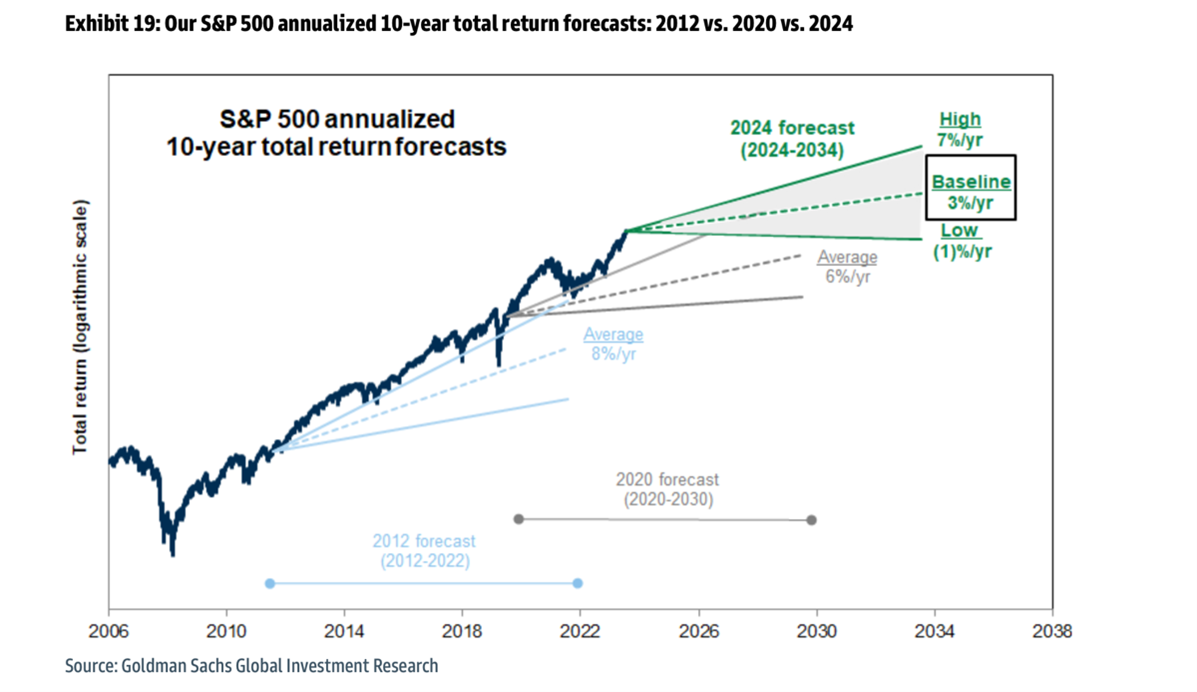

In October, a Goldman Sachs analysis caught my attention, predicting that the S&P 500’s returns over the next decade will be significantly lower than those seen over the past ten years. Over the previous decade, the index of the largest US companies grew by 233% (including dividends), amounting to an average annual return of 13%. By contrast, Goldman Sachs analysts expect the index to grow just 34% over the next ten years, yielding an annualised return of only 3%.

Figure 1. S&P 500 ten-year annualised return forecasts for 2012, 2020 and 2024. Source: Goldman Sachs.

Goldman Sachs analysts also do not rule out the possibility that the S&P 500 could be lower in ten years than it is today, projecting an annualised return ranging from −1% to +7%. This means that US stock markets could underperform the US bond market, where a ten-year bond currently offers a fixed yield of 4.3%.

A Goldman Sachs equity strategist told Bloomberg in an interview that while the US economy is currently strong and the Federal Reserve is lowering interest rates, they expect the index to deliver a 9% total return next year. Beyond that, however, they are less optimistic due to historically high stock valuations.

When investing, consider different scenarios

Nobel laureate in physics Niels Bohr once remarked, “Prediction is very difficult, especially when it’s about the future.” The Goldman Sachs analysis discussed earlier is less a warning of a bleak future that may await stock markets and more a example of how to approach risk effectively. Instead of focusing on a single figure, it is more informative to consider a range of possible outcomes.

For example, investing in a ten-year US government bond today provides near certainty that the return over the next decade will be 4.3%. By contrast, investing in US stocks could result in anything from a small loss to a return exceeding that of bonds. US government bonds are essentially risk-free, guaranteeing a fixed yield, whereas stock, which are significantly riskier, present the possibility of both gains and losses.

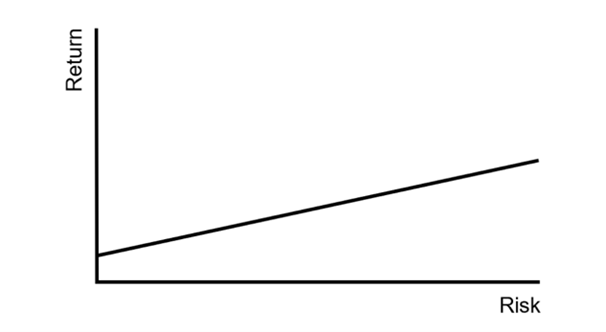

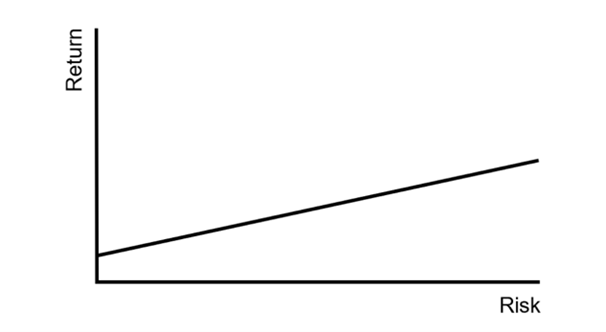

Renowned American investor Howard Marks described in his October memo how he approaches the relationship between risk and return. For decades, investment textbooks have presented this relationship as a linear line, illustrating how taking on greater risk yields higher returns.

Figure 2. The relationship between risk and return

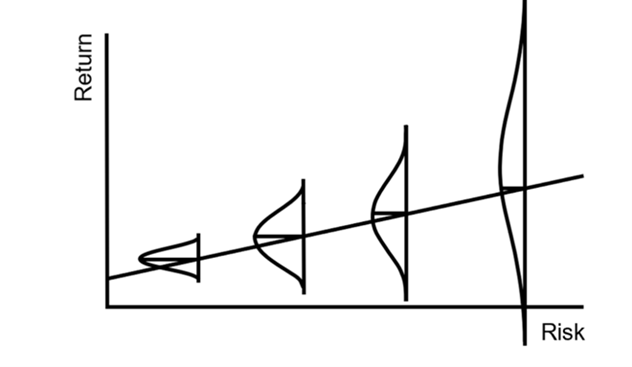

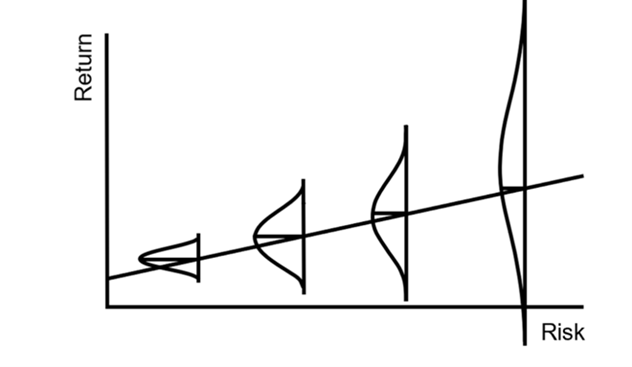

However, Marks argues that this explanation is inadequate because it overlooks the growing spectrum of possible outcomes as risk increases – a good result could be far better than forecasted, and a poor result much worse. Marks not only critiques the traditional view but also proposes a solution, suggesting a more accurate graphical representation of the relationship between risk and return.

Figure 3. The relationship between risk and return, as proposed by Howard Marks

We help grow pension assets by seeking to avoid major losses

When we launched LHV pension funds more than 20 years ago, we set three priorities for ourselves:

- Protect the assets accumulated in LHV pension funds from losses

- Preserve the purchasing power of the assets in LHV pension funds

- Achieve returns that outperform competitors.

In doing so, we have always adhered to the principle that high long-term returns can only be achieved by avoiding significant losses.

Pension assets are a reserve intended for the period of life when working age has ended and regular income from employment is no longer available. A reserve, by definition, should remain intact until it is needed. This means there is a limit to how much risk it is reasonable to take when investing the assets in a reserve.

Recently, I’ve received increasing feedback from colleagues that many clients’ main goal when choosing a pension fund is to maximise risk blindly. This has led me to wonder: Is this merely a sign of a prolonged period of market growth, where risks are forgotten as markets climb higher each day, or has the rapid spread of financial literacy and the popularisation of investing inadvertently or even deliberately overlooked some important, albeit less popular, concepts?

As Howard Marks notes in his memo, bond yields are currently higher than they were between 2009 and 2021, which should increase their relative attractiveness compared to stocks. Meanwhile, as highlighted by Goldman Sachs, stocks are at near-absolute valuation peaks compared to historical ratios, and returns over the next ten years could be significantly lower than over the past decade. All of this should prompt us to ask: Is maximum risk always the optimal strategy?

As in many areas of life, independent thinking is valuable in investing, and excessive simplification carries risks. Rules of thumb and generalisations – such as “stock markets offer better returns than bonds” or “younger investors’ portfolios should consist entirely of stocks” – are often helpful but should not be treated as dogma.

At LHV, our investment team has always factored both risks and expected returns into the investment process. We believe markets are cyclical, with times when taking risks is rewarding and times when caution is advisable. When bonds offer solid returns and stock markets are at all-time highs – not only in absolute price terms but also relative to corporate fundamentals – it may be wise to reassess your risks and potential returns. Higher risk does not inherently guarantee high returns; rather, it implies a wider gap between potential positive and negative outcomes compared to a lower-risk investment.